Translation: Masuda Discusses Game Freak History and the Gear Project

Junichi Masuda discusses Game Freak, 1989 to 2019

Written by Dr Lava • August 2, 2021

The following interview was originally published in the May 23rd, 2019 issue of Famitsu Weekly. Pokemon series director and producer Junichi Masuda sat down for a 5 page interview to mark 30 years since Quinty launched on the Famicom, making it Game Freak’s 30th birthday. Sword & Shield were only a few months from release, but those games aren’t mentioned even once — today, he wanted to talk about the company’s history, and where it’s going in the future. Highlights of this interview include Masuda and Tajiri’s personal history, how Tsunekazu Ishihara massively influenced Red & Green’s development, and what the Gear Project means for the future of Game Freak. This magazine also provides us with 11 pages of Capumon concept art.

All the scans used in this article were provided by my good friend and ally in the Pokemon preservation game, HiResPokemon, and I commissioned Japan-based interpreter Jacon Newcomb to translate the original Japanese into English. As usual, I’ve added lots of outside sources and some of my own commentary to provide additional context and relevant information to what’s discussed in this interview. I may have gone a little overboard on the outside sources this time to be honest — there’s about 20 pages of the Tajiri biographical manga, along with some sales charts and other materials. Well, hopefully you’ll feel it was worth all the effort. Okay, without further adieu, here’s the translation.

Game Freak’s Path to Worldwide Fame, As Told By Masuda

The Foundation of Game Freak’s Creative Process is “Fun”

“To start off, can you tell us how you came to work at Game Freak?”

Masuda: “Just by coincidence, I knew Tajiri from technical college — we were in the same year — and he introduced me to his company. They were looking for someone who could make video game music, so I gathered up all the original music I’d made up to that point and went to see Tajiri.”

“So you already knew Tajiri?”

Masuda: “Back then I was reading ‘Maikon Basic Magazine’ because I wanted to learn about programming, and I remember seeing something in there about a company called Game Freak that was publishing their own games. I might have seen Tajiri’s name in there too, and I thought ‘hold on, don’t I know him?'”

“What was your first impression of Tajiri and his team when you went to see them?”

Masuda: “They were self-publishing out of an ordinary apartment in Shimokitazawa, and at the same time, Tajiri was also working as a professional writer. So many people were going in and out of that apartment, that at first I couldn’t tell who was actually a Game Freak member (laughs). I think Sugimori was there too, but I didn’t recognize him at the time.”

“And that’s when you joined Game Freak right?”

Masuda: “By then I’d already graduated from technical school and found work as a programmer, but I started working in the Game Freak apartment on weekends. We talked a lot and I gave them my original music as a gift.”

“And development on Quinty started not long after that. Did you think they’d be able to pull it off?”

Masuda: “I’d never heard of people trying to make PC games or music on home computers before, so these guys were certainly something different (laughs). That said though, they knew what they were talking about when it came to programming and hardware, so I thought they were really incredible. They gathered together some programmers who knew a lot about hardware, and built all their development machines themselves.”

“Even the development machines? Then the publisher (Namco) sold the games you made and some became big hits. It’s a little hard to believe.”

Masuda: “We thought we were doing something incredible, but we weren’t interested in the sales side of things. We were just having fun playing our games together. Looking back, a lot of those games weren’t too well received. We were just making games we thought were interesting.”

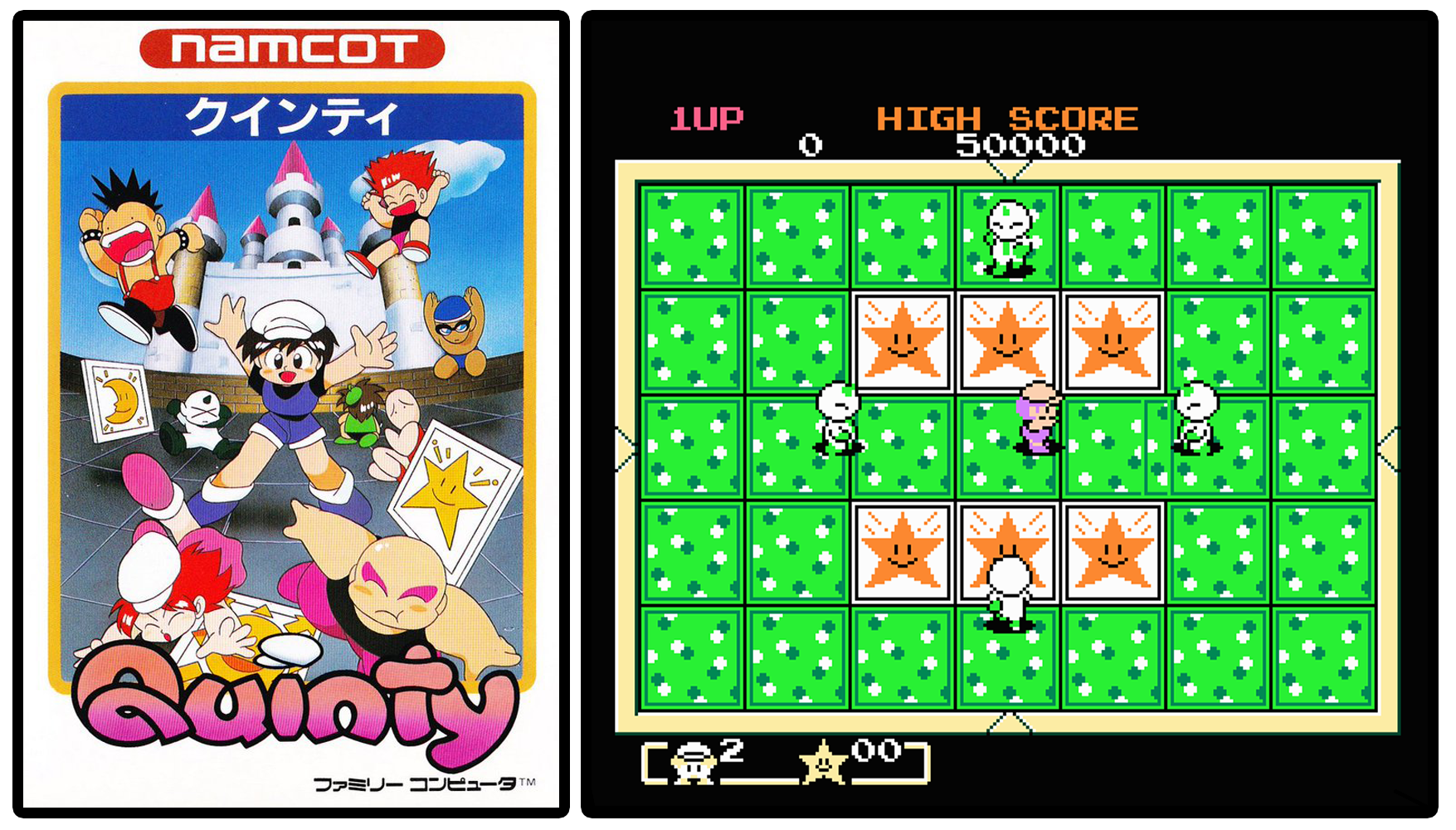

Dr Lava notes: Quinty was an action-puzzler with gameplay based on flipping floor tiles, released in June 1989 for the Nintendo Famicom. The protagonist Carton has to save his girlfriend Jenny, who’s been kidnapped by Carton’s younger sister Quinty, who’s jealous that her brother’s been paying too much attention to Jenny. When the game was localized into English, its name was changed to Mendel Palace and the story was changed — you play as Bon-Bon who rescues the princess Candy from being trapped in her own dream.

Game Freak’s second game Jerry Boy (mentioned below) was a platformer co-developed with System Sacom, and published by Sony for the Super Famicom in 1991. The easiest way to describe Jerry Boy is they wanted to make a game that’s essentially Kirby meets Donkey Kong Country, although it’s understandably not on par with the classics. When Jerry Boy was localized into English, its name was changed to Smart Ball, and its entire storyline and all the towns were removed. So if you have any interest in playing Jerry Boy, instead of SNES, I recommend emulating a fan translation of the Japanese original.

Jerry Boy 2 was in production and planned for release in 1994, but ended up getting cancelled before release, possibly due to Sony and Nintendo’s strained business relationship around this time. Reportedly, it was “99% finished.” ROMs can be found online, and it does indeed appear nearly finished (see below), with a much higher quality than the original.

Game Freak’s third game was Yoshi, their first financial hit — in fact, Pokemon’s development never would’ve been possible without the profits brought in by Yoshi. You can read more about Yoshi in this interview, as told by Satoshi Tajiri. Pokemon Red & Green were ultimately Game Freak’s eighth and ninth games. Okay, now back to this Famitsu interview.

The Six Year Journey from Capsule Monsters to Pokemon Red & Green

“Game Freak’s first game Quinty was born from a very simple idea, wasn’t it? What changed after its release?”

Masuda: “I’d have to say the biggest change was Game Freak’s transition into a company. The date was April 26th, 1989. I’d already quit my previous job, but waited until June to join Game Freak. I just needed a little time to stretch my wings (laughs). Then I joined Game Freak in charge of programming and music. It took us another two years to release our second game, Jerry Boy, and it was during this time we started drawing up our plans for Pokemon. But at the time we were calling it Capsule Monsters.”

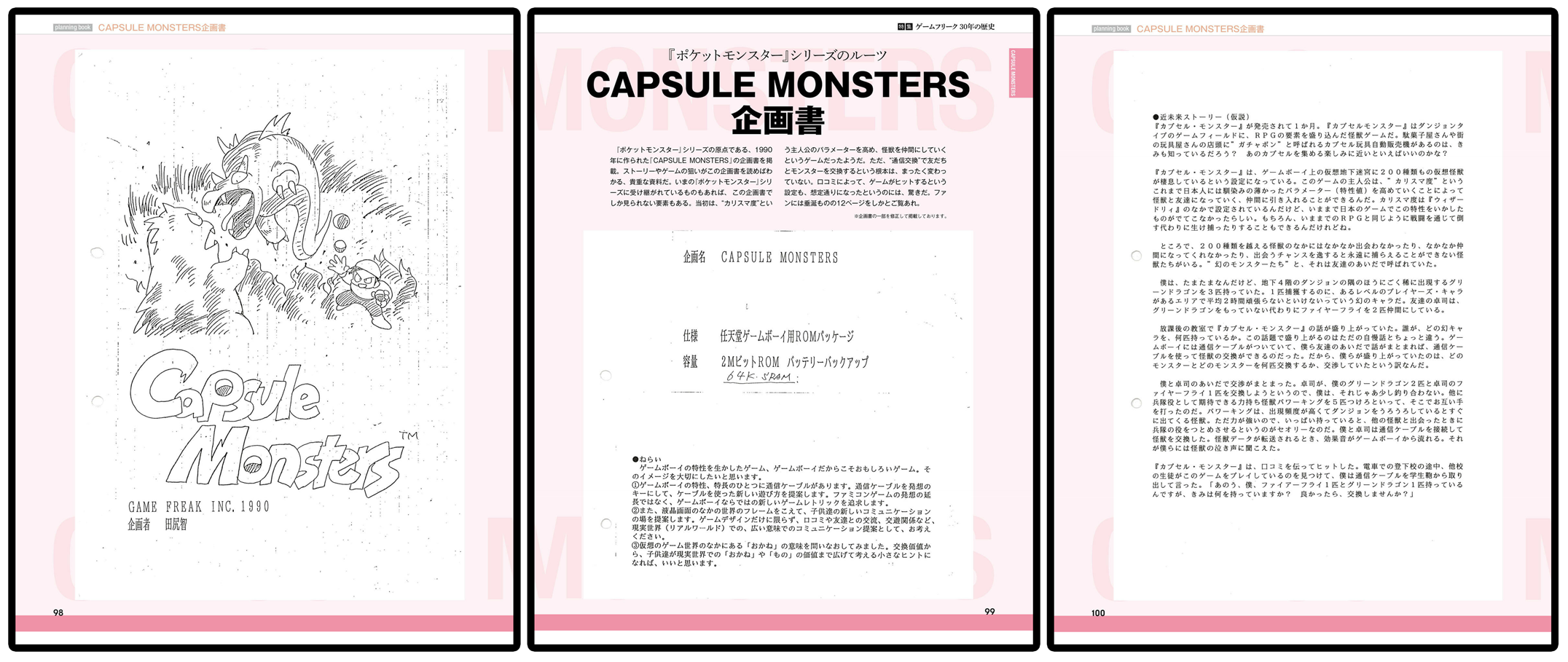

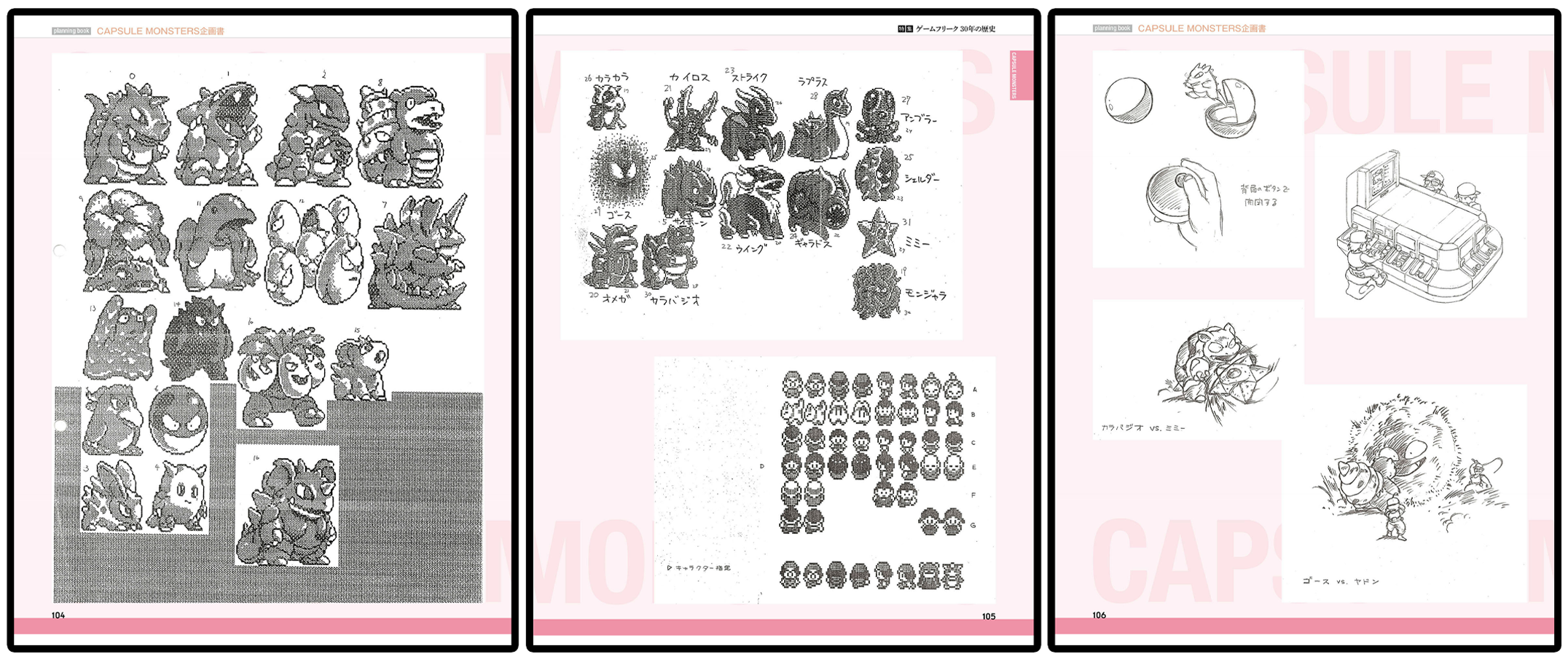

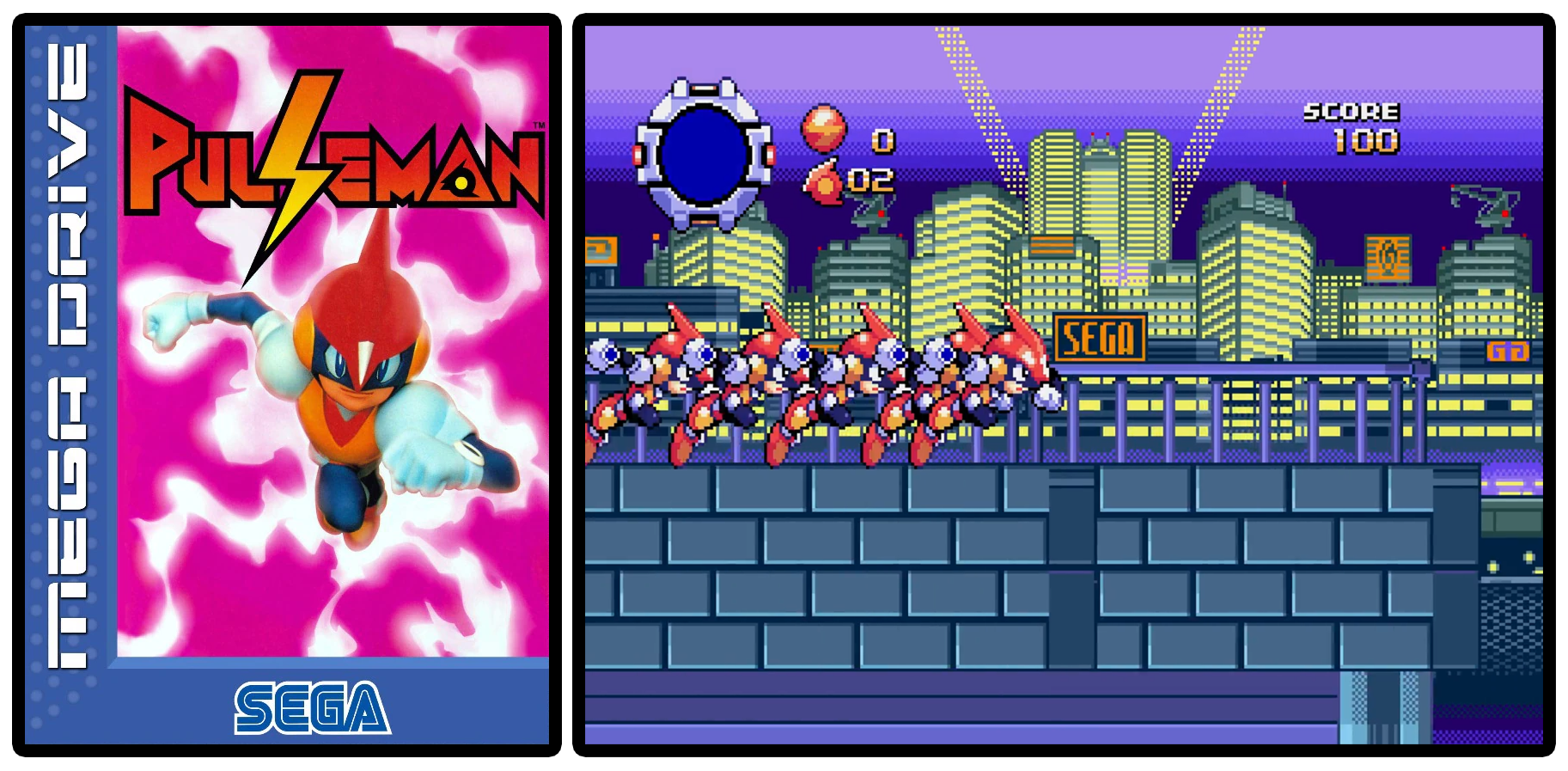

Dr Lava notes: There are 11 pages of design documents dating back to the Capsule Monsters era featured later in this Famitsu issue, so now’s probably a good time to include them in this article. Most of it was already published separately years earlier, but here they give us a whole bunch together, and in a pretty decent resolution. These pages of text were translated years ago by a now-inactive translator named Glitterberri — you can read her translation of these pages on her website.

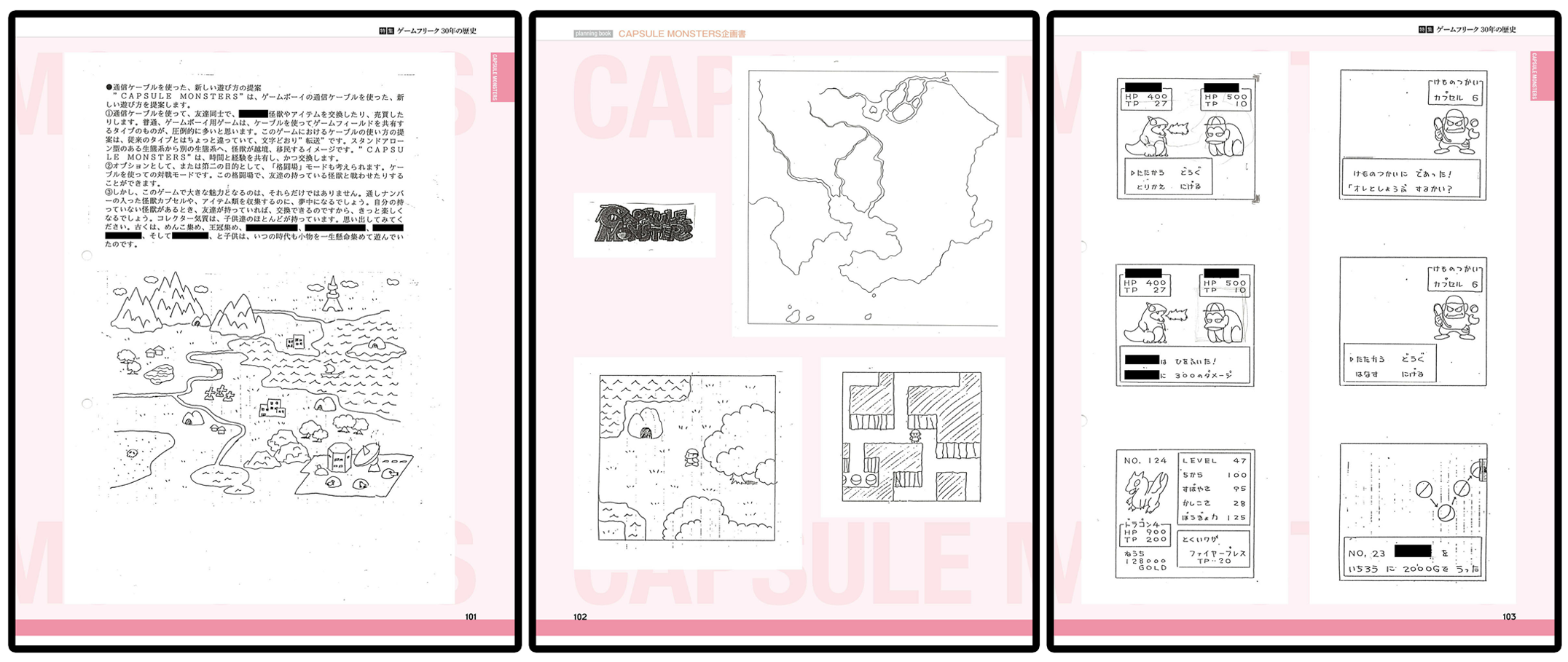

On these pages you can see early ideas for the Kanto region, along with some early concepts for Capsule Monster battles. Interestingly, the names Godzillante and Gorillaimo are censored in this print. Probably due to their similarities with Godzilla and King Kong. But this concept art has been printed before uncensored, so it’s a little curious Famitsu decided to censor it in this higher-resolution print.

Here we get a look at some of the earliest Pokemon ever created, including beta sprites for Scyther, Gyarados, and Arcanine — plus Omega, a Pokemon who got cut out of the game completely. If you zoom in closely on the machine on page 106, you can see the word Sony on the machine. Since Sony published some of Game Freak’s earlier games, they must have thought there was a good chance Pokemon would end up getting published by Sony as well. Just imagine a universe where Sony got the rights to Pokemon instead of Nintendo. Below you can read translations of the captions.

• Page 105, bottom: “Character specifications”

• Page 106, top-right: “The capsule is opened and closed with the button on the back”

• Page 106, middle-left: “Karabajio vs Mimii” (early scrapped Japanese names for Blastoise and Staryu)

• Page 106, bottom-left: “Gastly vs Slowpoke” (Slowbro was apparently called Slowpoke back then)

• Page 107, top: “Wanna trade for this guy?” / “For a Nidoran? Don’t mistake me for some kind of sucker!”

• Page 107, bottom: “HOTEL – Before going to bed, place any capsules you used in the energy basket. By the time you wake up, the monsters will be back to good health.” (an early concept for Pokemon Centers)

• Page 108, top-left: “Riding Lapras into the sea”

• Page 108, top-right: “Deep cave exploration”

• Page 108, bottom: “Monster graveyard” (probably early Pokemon Tower)

Okay now that we’re done covering this issue’s concept art, let’s get back to the Masuda interview.

“But Pokemon launched in 1996, were you really working on it for so long?”

Masuda: “Yeah it’s true, the initial concept really was that long ago, and it really did take six years to bring it to market (laughs). Of course, we were doing other things in the meantime, like making other games. It was the game Yoshi that really expanded our presence.”

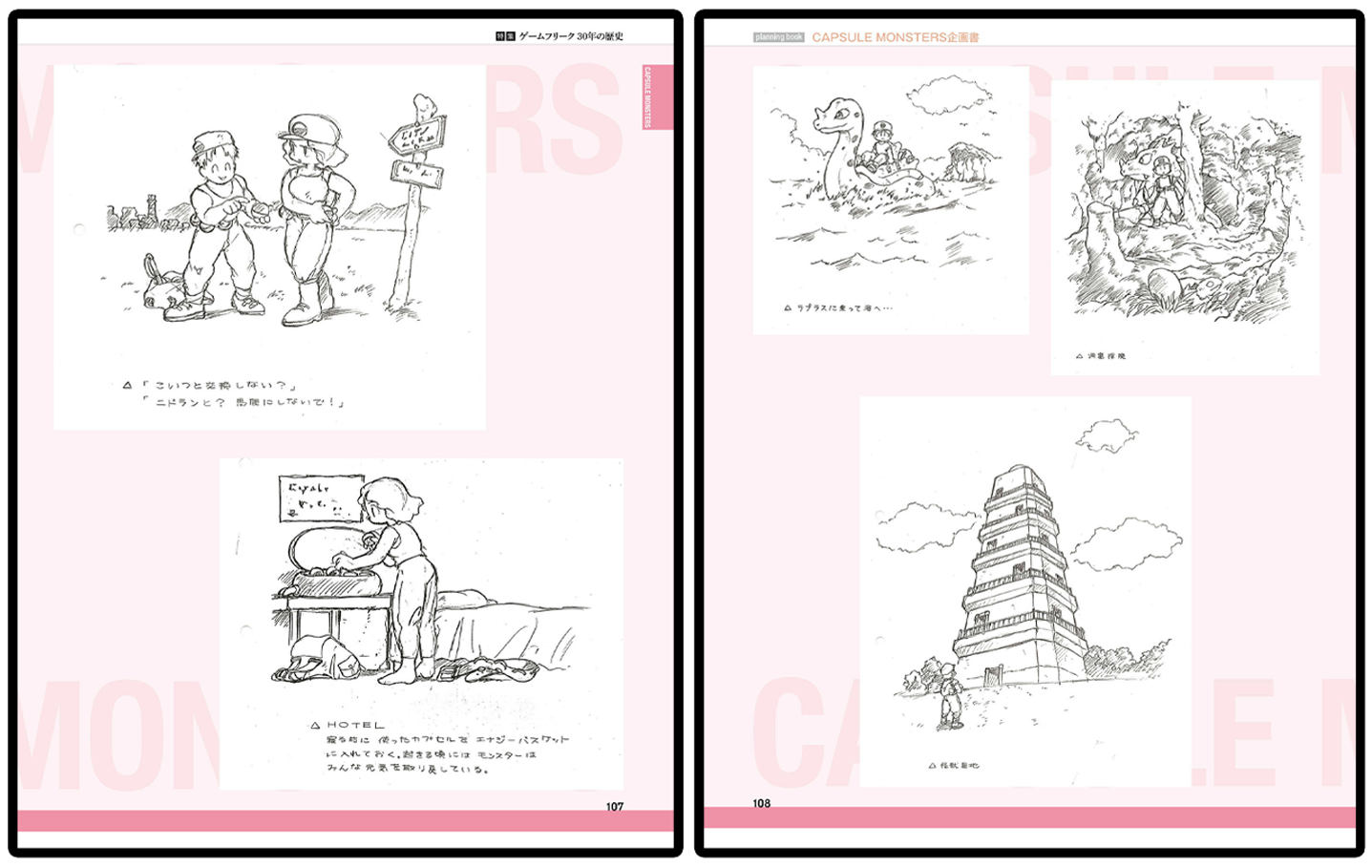

“The one requested by the late Gunpei Yokoi of Nintendo.”

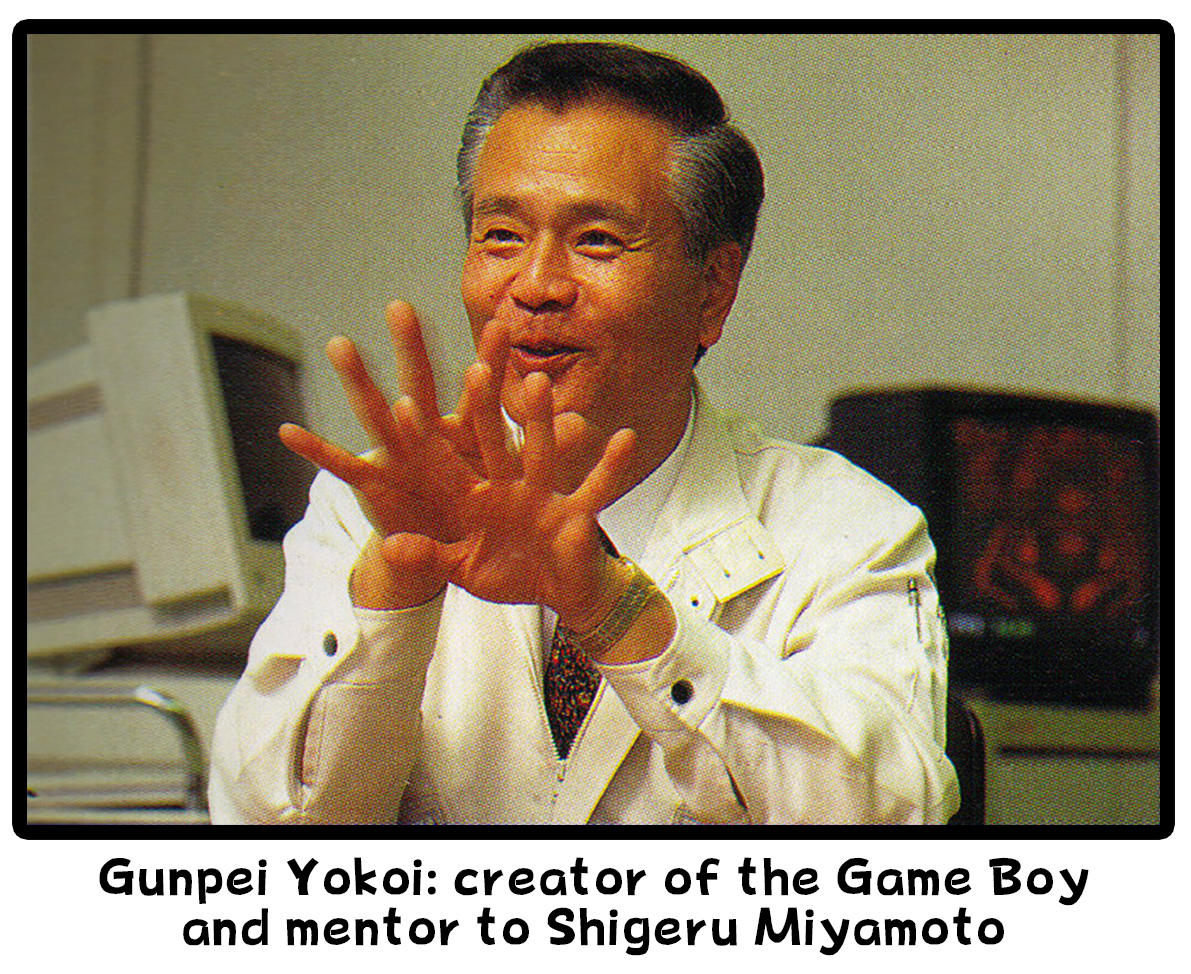

Masuda: “He came to Tajiri and asked him to ‘make a game centered around Yoshi.’ Everyone threw out some ideas, then we ended up going with Sugimori’s idea and developed a game based on that. We’re incredibly thankful it turned out to be a hit — it really saved us. Our company wouldn’t have survived the six years until Pokemon without some kind of income. After that, we continued making games like Mario & Wario and Pulseman, gradually gaining more development experience.”

“I imagine you needed all that time to see Pokemon Red & Green through to completion, but did you expect it would take six years when the concept was first proposed?”

Masuda: “It started with Tajiri saying ‘don’t you think it would be fun to trade monsters?’ after he saw a Game Boy Link Cable. Of course we thought his idea was fun and exciting… but we had a problem. We didn’t have any experience making RPG’s. We kept putting certain things aside to come back and fix later, but they kept piling up. For example, in the final game, HP is displayed with a meter, but at one point in development it was represented with text. We came up with 16 different status descriptions like ‘they’re still okay’ or ‘it’s gonna get bad pretty soon,’ but it wasn’t very interesting, so we scrapped it…..”

“Pokemon battles would be completely different if you kept it that way (laughs).”

Masuda: “Yeah it was kind of difficult to understand. But we worked things out through trial and error. Instead of having HP shown with words or numbers, we added a visible meter that decreases, which made it easy to see how much damage you’ve taken. If the meter gets really low, anyone can tell things aren’t going so well (laughs).”

“So you need the fortitude to throw something out, even if you’ve worked hard on it.”

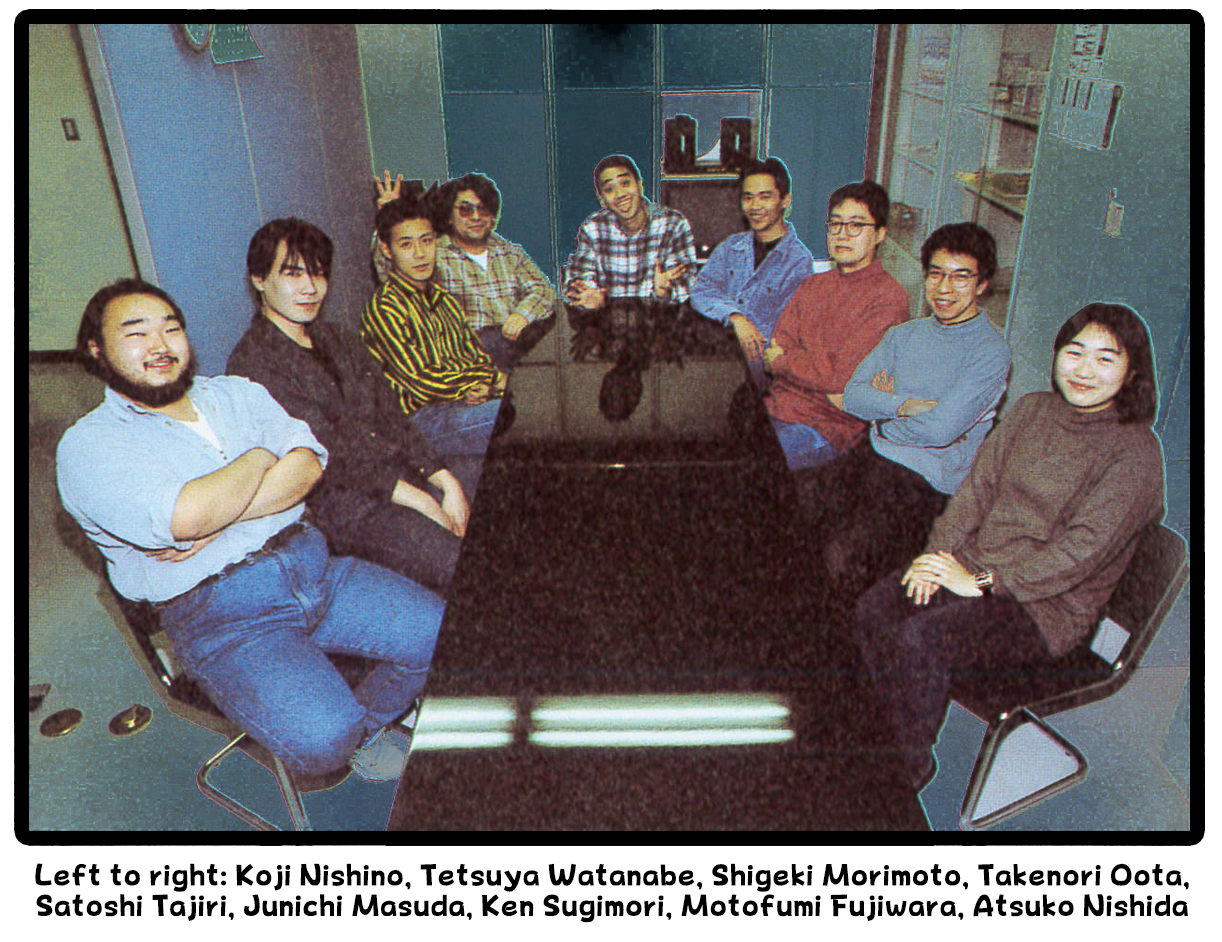

Masuda: “Yeah it feels wasteful to remove something you invested time into, but it’s unavoidable. The nine of us wanted to make Pokemon Red & Green absolutely perfect.”

“It’s hard to believe that there were only nine of you working on it.”

Masuda: “We spent so long working on it that the world changed around us before we were finished. The Game Boy was already seven years old by the time Pokemon made it into stores. The hardware we were using was already past its prime, and there were rumors it was gonna get phased out. The game we released two years before Pokemon, Pulseman, had music made through frequency modulation, but the Game Boy could only make three sounds, and it was black and white. Just looking at the specs, I can’t deny it was behind the times.”

I Won’t Let It End This Way

Overcoming Obstacles in Development

“But despite all that, the explosive success of Pokemon Red & Green completely revived the Game Boy market. For a game to be able to do that, that’s very impressive.”

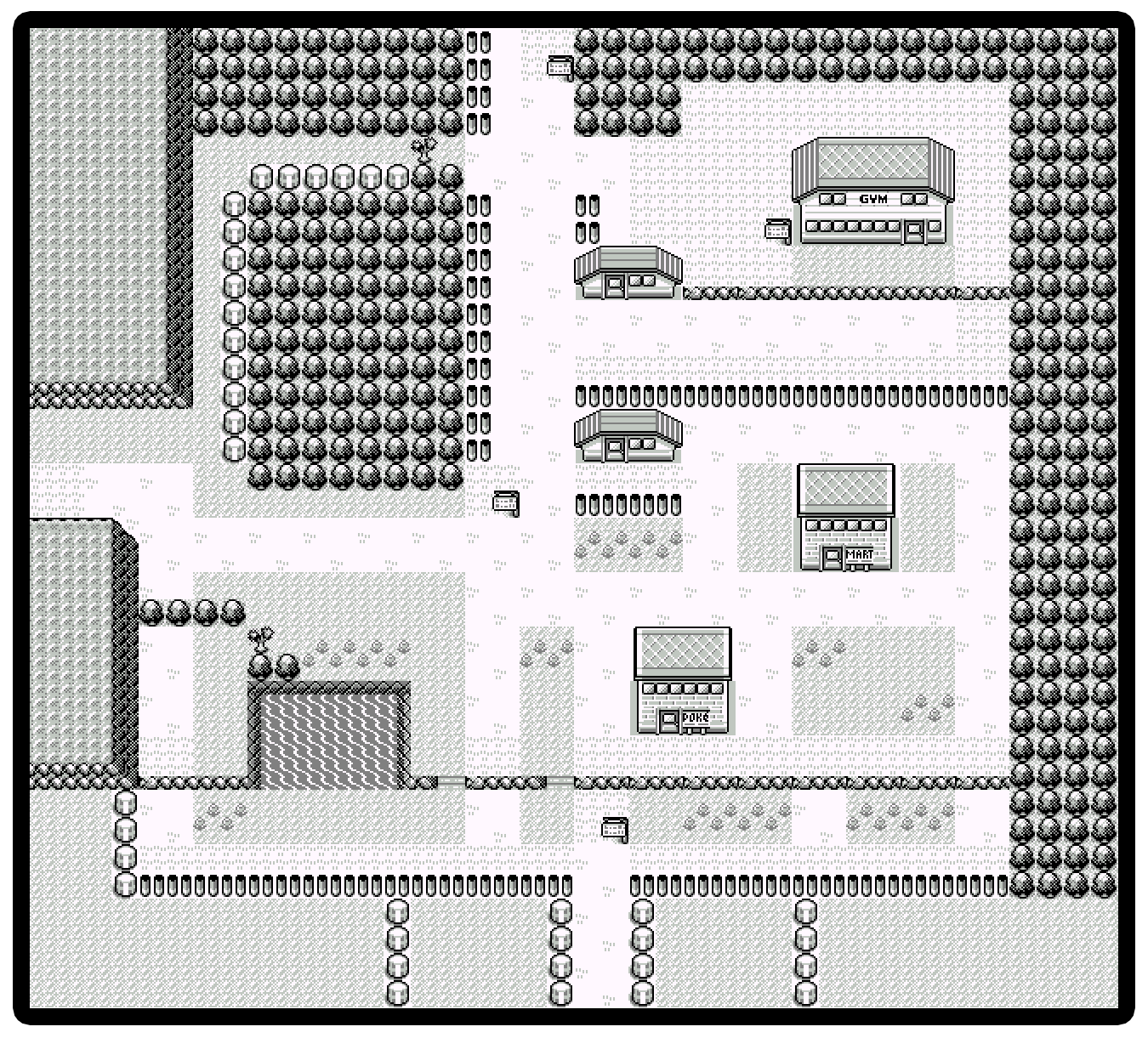

Masuda: “The biggest obstacle was finding ways to overcome the capacity limitations. There was so much content we wanted to squeeze into those two mega-hits…..! In order to fit all the Pokemon data, we had to make some cuts in other places. One of those cuts was the road system that connects the towns. We decided it wasn’t necessary to make the entire map one huge uninterrupted landmass, so we cut them up into small maps connected by gates. That and limiting the protagonist and Pokemon names to 5 characters, and the number of Pokemon moves to 4 each — that was all to save space.”

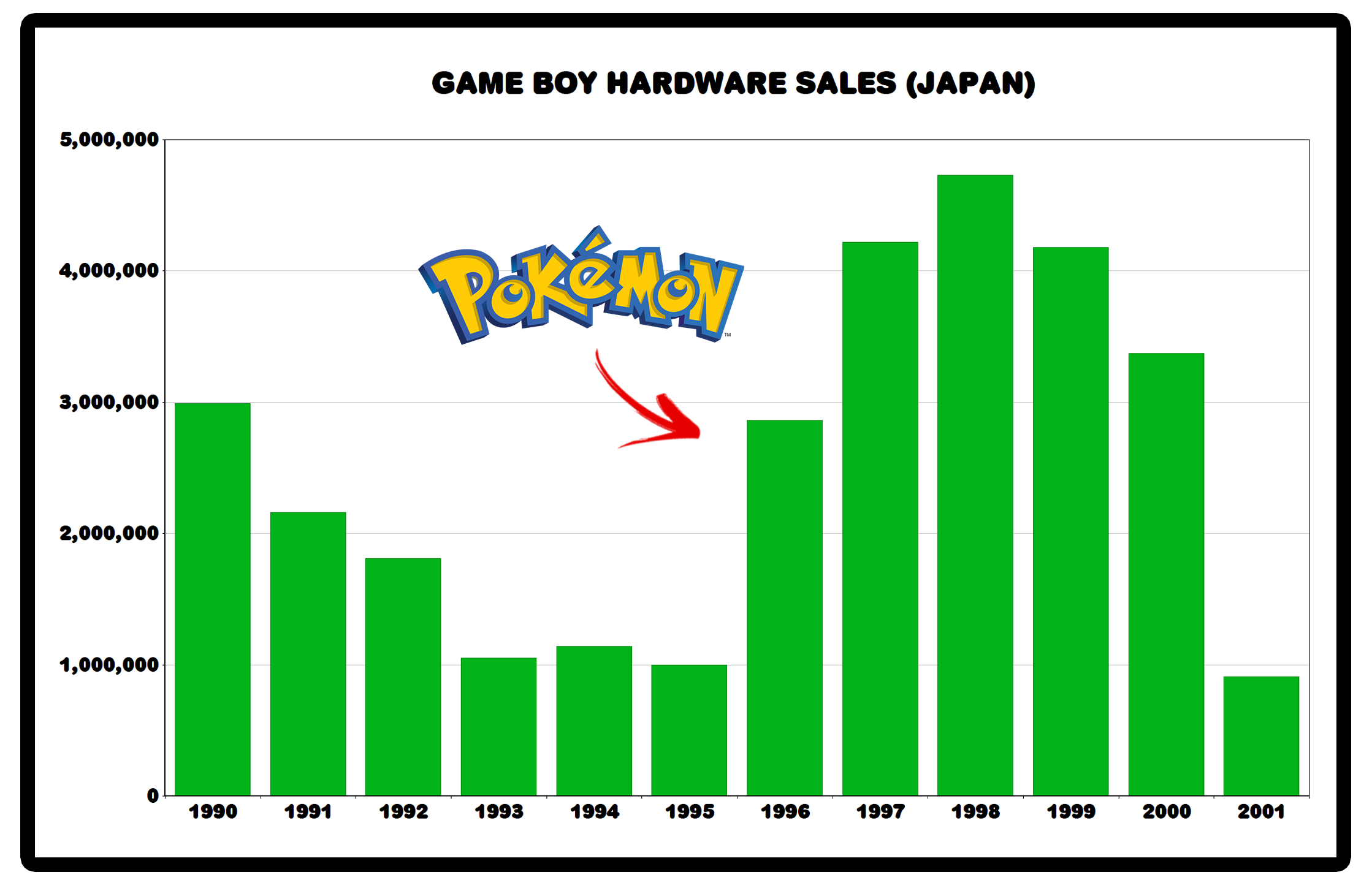

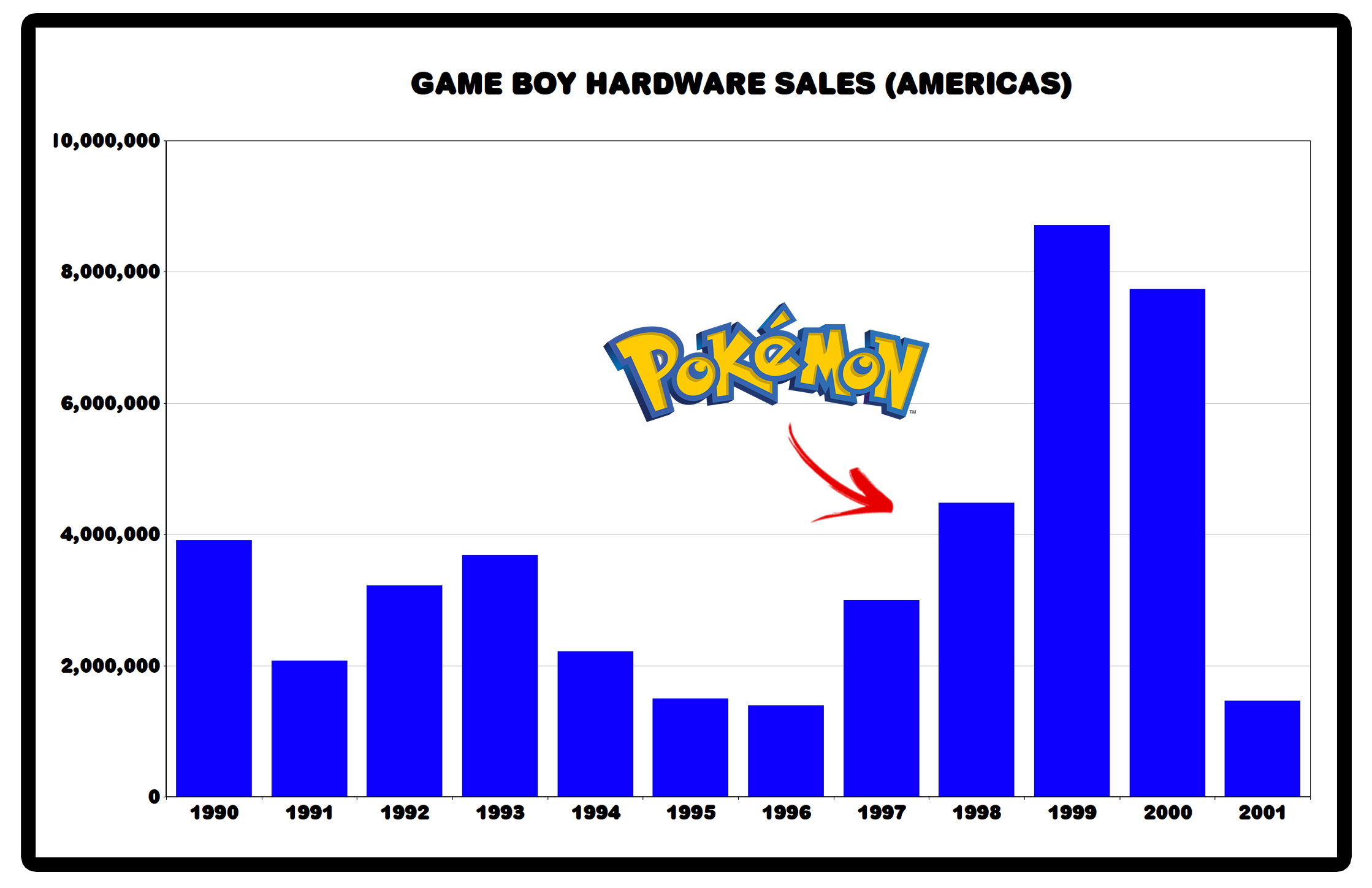

Dr Lava notes: I threw together these two graphs to help visualize just how much Pokemon revived the declining Game Boy market. You can see how many Game Boys sold each year in Japan — sales were on a steady annual downtrend as the system reached its expiration date, but then exploded in 1996 when Pokemon fever took the country by storm. As you can see below, the same thing happened in the Americas two years later (and pretty much every other region). By the end of its run, Gen 1 sold about 48 million copies worldwide. Eventually the Game Boy Advance launched and took Pokemon with it, so you can see GB sales fall off a cliff as soon as that happened.

“You don’t want to make the game less fun, but sometimes adding restrictions actually makes things more enjoyable right?”

Masuda: “We also tried to save space with some programming tricks. Like all the trees growing in the overworld — it looks like there are lots of trees, but it’s just the program loading the same tree over and over. We went through lots of trial and error finding similar ways to save space, and if we found the results acceptable, we implemented them.”

“Was it Tajiri who decided which shortcuts were acceptable and which ones weren’t?”

Masuda: “We all did it together. People getting overruled on whether or not something was acceptable didn’t really happen. We were a group of like-minded friends, and since there were only a few of us it was easy to work together. We gradually built on top of Tajiri’s original plan throughout development, every step of the way making sure not to lose sight of his original concept. That’s what’s so incredible about Tajiri.”

“So you were polishing up his original concept. Based on everything you’ve been sharing, it sounds like development went pretty smoothly……”

Masuda: “Well, I wish it’d gone smoothly. At one point we had a crisis after all the programmers quit at once.”

“All of them?! But you can’t develop a game without programmers.”

Masuda: “Even if we hired new people, it’s difficult to pick up where someone else left off with their unfinished programming. That’s why I took charge of it myself. I didn’t want us to have to throw out everything we’d created up to that point. I was friends with the guys who quit, and I understood their reasons for leaving, but it was still intensely frustrating. So I channeled that frustration into intense studying.”

Dr Lava notes: This incident where the programmers all quit at once is told from Tajiri’s perspective in the 2018 Satoshi Tajiri biographical manga (seen below). This manga was never localized into English, so I asked HiResPokemon to scan a few sections for me, which I paid to have translated, then I inserted the English text via Photoshop. I used most of these pages in a previous article — so my apologies for reusing them here — but they’re relevant again, and there’s also a fresh batch about Ishihara a little further down in this article. Just remember that manga’s read right-to-left, and you can click any image in this article to enlarge it and zoom in.

“I’ve heard you had help overcoming that situation.”

Masuda: “Yes, we received a lot of help as a company from Tsunekazu Ishihara (now CEO of the Pokemon company) and Shigeru Miyamoto (now Nintendo managing director), who were both at Nintendo. Ishihara in particular was fond of card games and used that insight to advise on how to add more depth to the battle system. To be honest, things like the Pokemon types, the link cable battles, and the Pokedex were all added later in development based on his suggestions. Tajiri’s flexibility and willingness to incorporate other opinions is another one of his great qualities.”

“Those are some pretty big features to be adding late in development.”

Masuda: “Ishihara also gave us some pointers on the story and setting. At first someone else was in charge, but it wasn’t the direction everyone else wanted, so Tajiri revised all the story stuff himself, and the final result was fantastic. Ishihara and Miyamoto both loved Pokemon, but first and foremost, it was Tajiri’s passion project.”

“You really had some great benefactors. So after all that work, Pokemon launched and became a smash hit. How did everyone at Game Freak feel about that sudden success?”

Masuda: “At the time, we were quickly approaching deadlines on other games we were developing, so we just kept on working without seeing the world’s reaction to Pokemon (laughs). We heard through the grapevine that Red & Green were gaining traction, but there wasn’t a singular moment where we suddenly realized how popular it was. After we released Gold & Silver, and we saw how much shelf space they were giving us at stores — that’s when it finally felt real.”

Dr Lava notes: If they’re even aware of his existence at all, a lot of Pokemon fans tend to think of Ishihara as just a suit, the guy who signs merch deals and stuff like that. And he certainly does those things first and foremost, but he actually had pretty significant creative contributions, especially early on — Pokemon types, link cable battles, and the Pokedex are no small things. The Tajiri biographical manga gives us a closer look at how Ishihara was responsible for Red & Green getting delayed six months so its story could be totally rewritten (I’ve omitted pages 123-128, as they’re irrelevant).

Starting the Gear Project Without Letting Pokemon’s Popularity Go to Waste

“Since Gold & Silver’s release, there’s been a lot of emphasis on taking the series even further, hasn’t there?”

Masuda: “At that point, Pokemon was getting more popular overseas, and Nintendo said we should make a third generation. We were in a situation where we didn’t have enough resources to make other games at the same time. Meanwhile, people saying ‘it won’t be popular anymore after Gold & Silver’ or ‘Pokemon’s already over.'”

“A lot of people have high expectations after something so popular, and there’s other people who won’t accept anything new.”

Masuda: “It was really emotionally taxing to make Ruby & Sapphire, but we knew we didn’t want it to come to an end, so we had no choice but focusing on the task at hand.”

“It must have been a nice break then when you released Drill Dozer in 2005?”

Masuda: “Indeed. Part of us just wanted to make an action game for a change (laughs). That’s how Game Freak got its start, but since Pulseman, it’d been 11 years since we made a traditional action game. The moment Sugimori said he wanted to make it, we were all just like ‘yeah let’s do it!’, so we allocated some developers to the project. They were pretty happy to be working on something different as well. Unfortunately though, the Nintendo DS had just released, and we’d made Drill Dozer for the Game Boy Advance. We should have timed it better… we learned our lesson from that.”

“So it was a similar feeling to when you released Pokemon Red & Green?”

Masuda: “Maybe for us at Game Freak, yeah. We still only had around 30 or 40 people at the company (laughs). We didn’t really know at the time, but the software we were using was lagging way behind the software other companies were using. I mean, we were still making sprite-based games in 2005, while other developers were using beautiful 3D graphics right…?”

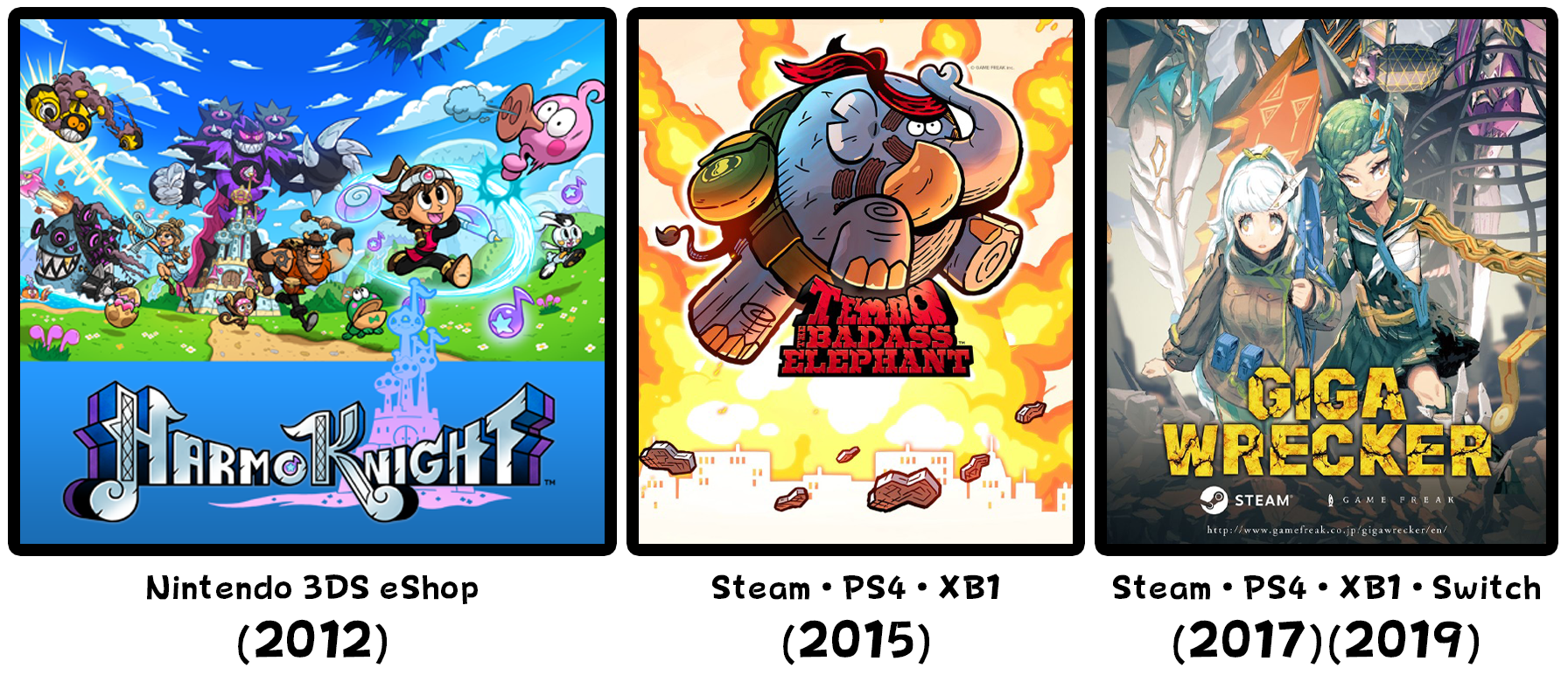

“I guess so (laughs). But I think being able to accept that and move forward is very Game Freak of you. After that you went back to making nothing but Pokemon games until you released HarmoKnight in 2012.”

Masuda: “That was the first title to come out of our new Gear Project system. I came up with the idea myself at some point, but gave up on it mid-development.”

“I suppose that sort of thing can happen sometimes.”

Masuda: “We’ll think something’s really interesting during the planning stage, then mid-development we’ll realize: ‘Huh, turns out this isn’t actually fun.’ But sometimes other things will seem boring in the planning stage, but after we make it, we realize it IS fun. That kind of thing happens a lot, and it’s those kinds of situations that led us to create the Gear Project. Game Freak members can submit as many ideas as they want for the planning stage, and we don’t judge them. It’s after the testing phase when we’ve actually made those ideas playable that we determine if it’s good or not. Letting people freely make what they wanna make encourages morale and creativity.”

“The Gear Project led to titles like Tembo the Badass Elephant and Giga Wrecker releasing on Steam. Pokemon fans must be surprised when they see you announce a new platformer.”

Masuda: “Yeah they’re pretty different. I’d say only 1 out of 50 Pokemon fans end up playing them. I’ve tried telling them ‘please try this one out,’ but it just didn’t seem to stick. We also started official Twitter and YouTube accounts last year. We’ve been putting more effort into promoting our games and sharing information about them. Before we mostly just focused on development and didn’t think too much about promotion, but now we’re taking that part seriously too. So with that said — Game Freak fans, please subscribe to our channel!…….. We actually just uploaded a new video to the official channel yesterday. I always ask people to subscribe, but maybe the way I was shouting it out was too intense (laughs). Seriously though, please watch the video.”

Dr Lava notes: There’s another Game Freak interview in this Famitsu issue, featuring Shigeru Ohmori, Kazumasa Iwao, Masayuki Onoue, and Masafumi Saito. I’ll probably publish it at a later date, but it’s sort of a low priority since they mostly talk about Game Freak’s non-Pokemon games. But I’ll summarize part of that interview here to help explain what the Gear Project is. Game Freak divides themselves into two separate teams, and Team 1 has a system in place that they call the Gear Project — which essentially means any team member can pitch an idea to the higher-ups and have their ideas listened to, so long as two other team members support their idea. They say quite clearly that Gear Project only pertains to Team 1, and it’s not used in Team 2.

In another interview, Masayuki Onoue explained how Game Freak’s focus has shifted away from Pokemon games in recent years, and towards creating new IP. He said: “There are two different production teams here, simply named Production Team 1 and Production Team 2. Team 1 is fully dedicated to Gear Project, while Team 2 is for the Pokemon operation. What that means is that Game Freak as a company is prioritizing Gear Project, which is production team number one, more than Pokémon in general. We are always trying to create something that is equally exciting, or more exciting than Pokémon.”

This insight into Game Freak’s priorities is probably why this Famitsu interview header is “Starting the Gear Project Without Letting Pokemon’s Popularity Go to Waste.” Game Freak doesn’t want to give up all the money Pokemon brings in, but it seems they’ve lost a lot of their enthusiasm over the past 25 years. And not only because they’re tired for the reasons you could expect anyone to get tired of doing the same thing for so long. Nintendo, the Pokemon Company, and various other partners are large shareholders in the Pokemon brand, which means Game Freak doesn’t have full creative control. Nor do they have financial control — a lot of the profits Pokemon generates have to be divvied up among those partners. On the other hand, they do have full creative and financial ownership when it comes to new IP. They’re probably hoping one of their new IP will become popular one day, so they can make a series out of it. But unfortunately for Game Freak, none of their non-Pokemon games have been particularly successful thus far… well, except for Yoshi back in 1991.

I’m sure it’s frustrating for modern day Pokemon fans to hear, but Game Freak’s higher-ups have been pretty clear on this topic on multiple occasions. Pokemon is handled by Team 2, while all their other games are developed by Team 1. And Team 1 is the priority. Their motivations are understandable… but disappointing, to say the least.

A Company Where Diverse Skill Sets Are Combined

The Focus isn’t Profit, it’s Making the World a Better Place

“Looking back over the past 30 years, what do you think is Game Freak’s biggest strength?”

Masuda: “One thing is how our top-to-bottom relationships aren’t too rigid, it’s a very open place. If that’s not the kind of work environment you’re in, it can be difficult to voice your opinions. If you’re afraid of your boss’ reaction, you won’t make an interesting game. If something in a game is bad, no one can speak bluntly and say it’s bad — so it’s our intention to maintain an environment where everyone can express their concerns.”

“When the higher-ups think that way, it must be easier for their subordinates to work.”

Masuda: “Another thing is that by letting people challenge themselves through the Gear Project, we prioritize ‘creating something interesting’ over everything else. Our philosophy is to develop games that make the world a better place, rather than ask questions like ‘how much profit is that going to make?’ and throw out ideas because of sales projections (laughs). Creative morale would suffer, and that would make it hard to create truly unique and ambitious IP.”

“Anyone can say that, but it’s hard to find development companies that follow through on that philosophy nowadays. That does seem to be one of Game Freak’s strengths. On the other hand, there must be some weak points you’ve identified?”

Masuda: “We haven’t been able to keep up with cutting-edge technology. Lots of staff members feel this way, and our development team is working to improve it. That doesn’t mean we should switch to making the latest version of everything, since we’re pretty accustomed to what we have, but if it means we can make things more appealing, we need to incorporate some newer technologies.”

“It’s a difficult balance.”

Masuda: “On one hand, we want to keep doing things the Game Freak way — but on the other hand, we can’t survive if we don’t upgrade our technology. For example, if we tried to make a battle royale like what’s been really popular lately, even though Game Freak has experience making action games, it would be difficult for us. I think we need to try harder, especially since we have so many ideas we want to put into action (laughs).”

“To change the subject… when it comes to game development, do you ever feel like your generation and the next generation of young people have a different way of thinking?”

Masuda: “Maybe to some extent. To give an example, our senior members grew up playing arcade games, so once they boot up a game, they want to get right into playing. But the younger members want to watch demo videos before they play. They’ve been raised in a different environment that’s changed how they think about games. When we hire new members, the first thing we do in training is debate what made Pokemon Red & Green such a big hit, and a lot of the young people will say it’s the plot, but historically that isn’t something we prioritized. Catching wild Pokemon, battling other trainers, the intrinsic fun of playing, thoroughly designing the gameplay — then after all that we look at the world-building and the plot. That’s how we do things.”

“So is this so-called Game Freakism something you teach in training?”

Masuda: “Yeah, we teach it. Basically, we want a wide variety of people. Someone whose skills are specialized in one area can’t make a game alone, but a jack-of-all-trades can’t specialize in anything. But if they put their strengths together, they can make something incredible. That’s the best way to run a company. We want Game Freak to be a place where people of all abilities come together to multiply their potential.”

“So even though you have your own way of doing things, you want all kinds of different members.”

Masuda: “Right. In this industry, you have to capture the attention of not only Japanese consumers, but all around the world, which is another interesting thing to consider. So Game Freak’s started bringing in international members from places like China and South Korea. They have interesting ideas, even if they bring with them a different set of values. Like James Turner, who directed HarmoKnight — he’s from England. The concept he pitched was unique, and entirely conveyed through manga storyboards. He still doesn’t speak Japanese too well, but the HarmoKnight concept was more about communicating a gaming spirit than words, so we saw potential in his proposal. He also contributed as an art director and character designer, and since his style is pretty different compared to Japanese people, it gave the game more originality.”

“So he used manga to express what he couldn’t say with words. Indeed, it’s a concept that a Japanese member would struggle to come up with. The gaming industry changes fast, so diversity is important to maintain flexibility.”

Masuda: “The gaming industry will of course continue to advance technologically, and I think even the concept of what’s fun will change as well. In this new era, I hope to go with the flow and continue making great games with our new members. If anyone’s interested in joining Game Freak, please apply on our website’s recruitment page (laughs).”

Closing Comments

And that wraps up Junichi Masuda’s brief historical recap of Game Freak’s beginning, and explanation of Game Freak’s present (in 2019). But of course there’s lots more interviews with tons more information, and you can find translations of any of those interviews on this website’s homepage. If you’d like to contact me for any reason, or just keep up-to-date on new translations and videos, the easiest place to find me is on Twitter.

I wanna give a big thanks to my Patreon supporters, whose $5 a month make these sorts of translations possible, and also held fund all the other various costs associated with running this website. This article is currently only available to read for my Patreon supporters, so if you’re reading this, you’re probably already one of my supporters. There’s about ten more translations available on Patreon, which you can read by clicking here. Cheers.

Read More Pokemon Translations:

• Interview: Tajiri and Ishihara discuss Game Freak before Pokemon

• Developer Blog: Pokemon Anime Was Written Under the Influence

• Interview: How Game Freak Creates Pokemon

Videos About Pokemon History:

• Translation: Sugimori Explains Gen 5 Beta Pokemon

• Cut Content: Gen 4 and 5’s Scrapped Lock Capsule Event

• Cut Content: Gen 4’s Internal Data and Cut Content